Operation Glimmer was one of three clever deception tactics used by Allied forces on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Along with Operations Taxable and Big Drum, it aimed to confuse German radar and draw attention away from the real Normandy landing sites. The Royal Air Force created false radar signatures by dropping metal strips (codenamed “Window”) along the French coast near the Pas-de-Calais region. The metal strips simulated an entire invasion fleet where none actually existed.

These tactical deceptions played a crucial role in the success of D-Day. While the main Allied forces stormed the beaches of Normandy, Operation Glimmer helped convince German commanders that another landing might occur elsewhere. This split the German defensive response and created valuable confusion during the critical early hours of the invasion.

The genius of Operation Glimmer lay in its simplicity and effectiveness. Using relatively simple technology, the Allies managed to create a phantom invasion force that appeared real on German radar screens. This operation demonstrates how military deception could be just as important as direct combat in turning the tide of World War II in Western Europe.

Historical Context of Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord represented the culmination of Allied planning and preparation for a decisive strike against Nazi Germany’s occupation of Western Europe. The massive amphibious and airborne assault launched on June 6, 1944 (D-Day) marked a turning point in World War II.

The Strategic Importance of Normandy

Normandy offered several critical advantages as the invasion site for Allied forces. The region’s beaches provided suitable landing zones for amphibious forces, while its proximity to England allowed for shorter supply lines and air cover.

The Allies deliberately chose Normandy over the more obvious Pas-de-Calais area, which represented the shortest crossing point from England to France. This decision exploited German expectations, as Hitler’s forces concentrated their strongest defenses at Calais.

Normandy’s inland terrain of hedgerows and small fields could slow German counterattacks and provide cover for Allied troops. The location also positioned Allied forces to drive toward Paris and ultimately into Germany’s industrial heartland.

Allied Preparations for D-Day

The Allies undertook extensive preparations for Operation Overlord beginning in 1943. Military planners assembled an invasion force of over 156,000 troops, supported by nearly 7,000 naval vessels and 11,000 aircraft.

Training exercises like Operation Tiger rehearsed landing procedures, though sometimes with tragic results. Allied forces developed specialized equipment including amphibious DD tanks, DUKW amphibious vehicles, and Mulberry artificial harbors.

Intelligence operations were crucial to success. The Allies implemented an elaborate deception plan called Operation Bodyguard, which included Operation Fortitude to convince Germans that Pas-de-Calais remained the main invasion target.

Supply stockpiling reached massive proportions, with millions of tons of equipment, ammunition, food, and medical supplies gathered in southern England before the invasion.

German Defenses and Occupation in France

Nazi Germany occupied France since 1940, establishing the “Atlantic Wall” – an extensive defensive network along the French coastline. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel significantly strengthened these defenses in early 1944.

The Atlantic Wall featured concrete bunkers, artillery positions, machine gun nests, and extensive minefields. Rommel ordered the placement of beach obstacles and “Belgian Gates” to block landing craft, along with millions of mines on beaches and fields.

German forces in France included approximately 60 divisions, though many were under-strength or comprised of non-German troops with questionable morale. The elite Panzer divisions represented the greatest threat to Allied success.

Hitler’s command structure complicated German defense preparations, as disagreements between Rommel and von Rundstedt created strategic confusion about whether to meet the invasion at the beaches or counterattack inland.

Deception Efforts Leading to D-Day

Allied forces created an elaborate web of deception ahead of the D-Day invasion to mislead Nazi Germany about the actual landing location. These efforts involved fake armies, inflatable equipment, and carefully orchestrated operations designed to keep German forces away from Normandy.

Operation Bodyguard and Its Sub-Operations

Operation Bodyguard served as the overarching deception plan for the D-Day invasion. Started in 1943 by the London Controlling Section, this masterful strategy convinced German High Command that the Allies had more troops in Britain than they actually did.

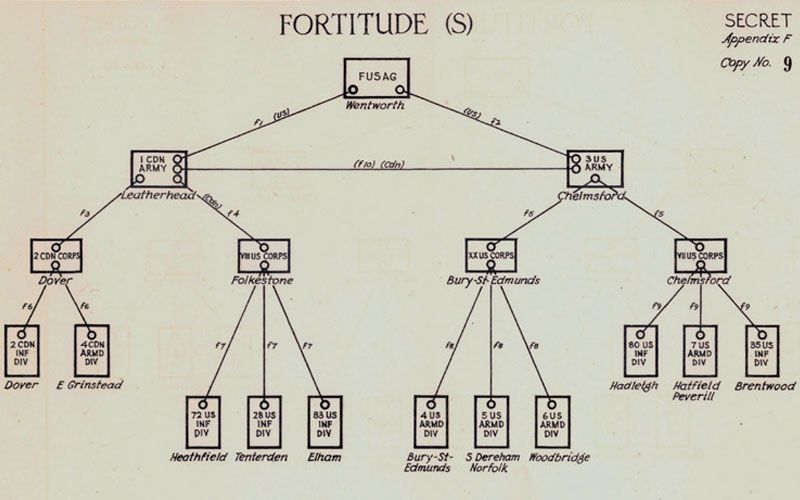

The most successful component was Operation Fortitude, which had two parts: Fortitude North and Fortitude South. Fortitude North suggested an invasion of Norway, while Fortitude South indicated the main attack would target Pas de Calais rather than Normandy.

This elaborate plan included the creation of a fictional army—the First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG)—supposedly led by General George Patton. The Allies constructed fake military camps, used rubber tanks and vehicles, and generated false radio traffic to support this illusion.

Double agents played a crucial role by feeding false information to Nazi intelligence. The “Double Cross System” controlled all German spies in Britain, turning them into counterintelligence assets.

Roles of Operation Glimmer and Operation Taxable

Operation Glimmer and Operation Taxable were critical naval and air deception efforts conducted during the D-Day invasion. These operations created phantom invasion fleets to distract German forces from the actual landing sites.

Operation Glimmer involved six Short Stirling bombers with two reserve aircraft. These planes flew patterns over the Channel toward Cap d’Antifer, dropping strips of aluminum foil called “Window” (chaff). This material created radar signatures mimicking a large naval fleet approaching the coast.

Meanwhile, Operation Taxable used Lancaster bombers following precise flight paths while dropping similar radar-reflecting materials. This operation simulated a convoy heading toward Pas de Calais.

Together, these operations convinced German radar operators they were tracking major invasion fleets heading toward locations away from the actual Normandy beaches. This deception kept German reinforcements away from the real landing zones during the critical early hours of the invasion.

The Use of Decoy Operations

The Allies employed numerous physical decoys to strengthen their deception strategy. Inflatable rubber tanks, fake landing craft, and plywood aircraft were positioned strategically to be spotted by German reconnaissance planes.

Engineers constructed elaborate mock military bases with canvas and wood structures. At night, these fake installations featured controlled lighting patterns that mimicked active military facilities when viewed from above.

Parachuting dummies, nicknamed “Ruperts,” were dropped away from actual paratroop landing zones. These cloth figures, equipped with small explosive devices to create noise and flashes, scattered German defenses by suggesting widespread airborne landings.

Naval decoys included small craft equipped with sound systems broadcasting recorded noises of larger vessels. Special naval units conducted diversionary operations with smoke screens and simulated landing preparations at non-target beaches.

These physical deceptions complemented the broader strategic deception plan, creating a multi-layered illusion that successfully divided German defensive resources and attention during the critical D-Day operations.

The Execution of Operation Glimmer

Operation Glimmer was a critical deception tactic executed during the D-Day invasion to confuse German radar systems. It created the illusion of an approaching Allied invasion fleet headed toward Pas-de-Calais rather than Normandy.

The Implementation on June 6, 1944

Operation Glimmer launched in the early hours of June 6, 1944, as a key component of the Allied deception strategy. Six Short Stirling bombers with two reserve aircraft took off from England and flew toward the French coast near Pas-de-Calais.

The bombers flew in precise patterns at low altitudes over the English Channel. Their mission was to simulate the radar signature of a large invasion fleet approaching a different location than the actual Normandy landing sites.

The timing was carefully coordinated with the main D-Day operations. As Allied forces were landing on Normandy beaches, Operation Glimmer was actively misleading German radar operators hundreds of miles away.

Techniques and Technologies Used

The primary technology employed in Operation Glimmer was thin strips of aluminum foil known as “Window” or “Chaff.” These metallic strips were specifically designed to create false radar echoes when dropped from aircraft.

RAF bomber crews released these strips in careful patterns that mimicked the radar signature of numerous ships moving across the Channel. The technique was remarkably effective, as German radar operators could not distinguish between actual vessels and these fabricated signals.

The operation also used specialized flight patterns. Aircraft maintained consistent speeds and headings to create convincing radar tracks that resembled a naval convoy. This prevented German forces from determining that the signals were merely a deception.

Radio transmissions were another key element. Operators broadcast fake communications to reinforce the impression of a large fleet, completing the illusion that a major landing was imminent at Pas-de-Calais.

The Beaches of Normandy and Landing Operations

The Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, involved carefully planned landing operations across five designated beach sectors. These coastal areas became the focal points where thousands of troops stormed ashore to establish crucial beachheads against German defenses.

Sector Designations and Assault Areas

The Normandy invasion targeted five main beaches, each with its own code name. Utah and Omaha beaches were assigned to American forces, while British troops landed at Gold and Sword beaches. Canadian forces were responsible for Juno beach.

Utah Beach, the westernmost landing site, stretched approximately 3 miles along the Cotentin Peninsula. Omaha Beach extended about 5 miles between the villages of Vierville and Colleville.

The British sectors included Gold Beach (5 miles long near Arromanches) and Sword Beach (the easternmost landing site). Juno Beach, assigned to Canadian forces, lay between Gold and Sword.

This massive operation involved over 7,000 ships and landing craft carrying approximately 195,000 naval personnel. The beaches were selected based on their access to inland routes and potential for rapid expansion of the beachhead.

Analysis of Omaha and Sword Beach Defenses

Omaha Beach featured some of the most formidable defenses encountered during D-Day. The Germans had established multiple layers of obstacles, including:

- Concrete bunkers positioned on bluffs overlooking the beach

- Machine gun nests with interlocking fields of fire

- Beach obstacles like “Czech hedgehogs” (metal X-shaped barriers)

- Extensive minefields both on the beach and underwater

These defenses contributed to the heavy American casualties at Omaha, where troops faced steep cliffs and well-protected German positions.

Sword Beach, while still heavily defended, had a different defensive profile. Its flatter terrain offered less natural protection for German forces. However, it featured:

- Concrete gun emplacements

- A network of trenches and fortifications

- Anti-tank ditches to prevent armored advances

Both beaches represented different challenges that required specialized assault tactics and equipment to overcome.

Landing Strategies and Allied Troop Movements

The Allied landing strategy relied on careful coordination between naval bombardment, air support, and amphibious forces. Initial waves included specialized units tasked with clearing beach obstacles and creating paths through defensive barriers.

At Omaha Beach, the first assault waves landed at approximately 6:30 AM, with troops from the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions facing immediate heavy fire. Their advance was slowed by strong currents that pushed landing craft off target.

British forces at Sword Beach deployed amphibious DD tanks (designed to “swim” ashore) ahead of infantry units to provide cover. The landing began at 7:25 AM with commandos and infantry working to push inland toward Caen.

The landing operations followed this general pattern:

- Pre-landing naval and aerial bombardment

- Arrival of engineers to clear obstacles

- Main infantry landings with armor support

- Establishment of beachheads and movement inland

Despite varying levels of resistance, all five beaches were secured by day’s end, creating a foothold for the Allied liberation of Western Europe.

Key Military Figures and Leadership

Operation Glimmer’s success depended on the strategic vision of high-ranking officers who coordinated this complex deception as part of the larger D-Day invasion. Leadership decisions at multiple levels shaped both Allied and Axis preparations for the Normandy landings.

Supreme Allied Command and Dwight D. Eisenhower

General Dwight D. Eisenhower served as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. This made him ultimately responsible for all D-Day operations, including deceptions like Operation Glimmer. He earned his fifth star during World War II, reflecting his crucial leadership role.

Eisenhower faced enormous pressure making the final decision to launch the Normandy invasion. Weather conditions were questionable, yet delay would have complicated the entire operation.

Eisenhower’s leadership style emphasized cooperation among Allied forces. He appointed Air Marshal Arthur Tedder as Deputy Supreme Allied Commander, creating a command structure that balanced American and British interests.

Under Eisenhower’s command, Operation Glimmer was integrated with other deception measures like Operations Taxable and Big Drum. These coordinated efforts successfully diverted German attention from the actual landing zones.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Role in German Defenses

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, known as the “Desert Fox,” commanded German forces responsible for defending the Atlantic Wall against Allied invasion. Hitler appointed Rommel to strengthen coastal fortifications in early 1944.

Rommel believed the invasion would succeed or fail on the beaches. He advocated positioning Panzer divisions near the coast for immediate counterattack rather than holding them in reserve.

The German high command remained divided on defense strategy. Rommel wanted tanks near the beaches, while other generals preferred keeping armored reserves inland for a concentrated counterattack.

Rommel’s forces were directly targeted by deception operations like Glimmer. These operations successfully confused German commanders about the true invasion location, preventing Rommel from concentrating his forces effectively.

General Patton and Allied Ground Strategies

General George S. Patton played a unique role in D-Day deceptions despite not participating in the initial landings. German intelligence considered Patton America’s best field commander and expected him to lead the main invasion force.

Allied planners leveraged this perception by placing Patton in command of the fictional First US Army Group (FUSAG). This phantom army, supported by deceptions like Operation Glimmer, convinced Germans that the main attack would target Pas-de-Calais.

Patton maintained a high public profile in England to reinforce this deception. His presence helped make Operation Glimmer more convincing to German intelligence analysts.

After the successful Normandy landings, Patton would later take command of the Third Army. His aggressive combat leadership proved vital during the breakout from Normandy and subsequent campaigns across France.

Support Operations and Allied Coordination

Operation Glimmer worked alongside multiple coordinated Allied efforts during the D-Day invasion. These operations involved complex coordination between airborne, naval, and ground forces from multiple Allied nations to ensure the success of the Normandy landings.

Airborne Assaults and Paratroopers

Allied airborne operations formed a critical component of the D-Day strategy. Hours before the beach landings, approximately 24,000 American, British, and Canadian paratroopers dropped behind enemy lines. Their mission was to secure key bridges, roads, and towns to prevent German reinforcements from reaching the beaches.

The U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions landed in areas west of Utah Beach, while British 6th Airborne Division secured the eastern flank. Many paratroopers landed off-target due to navigational errors and anti-aircraft fire.

Some units used dummy paratroopers (codenamed “Ruperts”) to create confusion among German forces. These cloth dummies were dropped alongside recordings of gunfire to simulate a larger invasion force, supporting the deception created by Operation Glimmer.

Amphibious Invasion Forces

The amphibious assault, codenamed Operation Neptune, served as the naval phase of the broader Operation Overlord. This massive seaborne invasion involved nearly 7,000 vessels of various types.

Landing craft delivered troops to five designated beaches: Utah and Omaha (American), Gold (British), Juno (Canadian), and Sword (British). Naval bombardment from battleships and cruisers targeted German coastal defenses before the landings.

Operation Glimmer directly supported these amphibious forces by creating a phantom invasion fleet off Pas-de-Calais. Six Short Stirling bombers dropped thousands of metal strips (“Window” or “Chaff”) that mimicked a large invasion fleet on German radar.

This deception helped keep German forces positioned away from Normandy during the critical first hours of the invasion.

Contribution of U.S., British, and Canadian Troops

The multinational force that executed the D-Day invasion demonstrated remarkable coordination. American forces led by General Omar Bradley landed at Utah and Omaha beaches, facing especially heavy resistance at Omaha.

British troops under General Miles Dempsey secured Gold Beach and parts of Sword Beach. The Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Rod Keller, successfully landed at Juno Beach despite strong German defenses.

British and Canadian forces worked in close coordination with Operation Glimmer, which was primarily executed by RAF bomber crews. Their deception efforts helped protect all landing forces by keeping German reserves focused on the Pas-de-Calais region.

The success of these combined operations demonstrated the effectiveness of Allied planning and coordination across multiple nations, services, and tactical objectives.

The Aftermath of Operation Glimmer

Operation Glimmer, along with its sister deception Operation Taxable, successfully confused German radar systems during the critical early hours of the D-Day landings. The strategic impact of these deceptions rippled through both the immediate battle outcomes and long-term war efforts.

Immediate Impacts on D-Day’s Success

Operation Glimmer achieved its primary objective by diverting German attention away from the actual landing sites in Normandy. The clever use of “Window” (metal strips dropped to create false radar readings) convinced German commanders that a significant naval force was approaching the Pas-de-Calais area.

This deception succeeded in keeping German reinforcements away from the actual invasion beaches during the crucial first hours of June 6, 1944. Several German divisions remained in position near Calais rather than moving to counter the real threat.

The confusion created by Operation Glimmer gave Allied forces valuable time to establish beachheads with reduced opposition. While over 4,000 Allied troops still lost their lives during the initial landings, military historians agree the casualty count would have been significantly higher without these deception operations.

Long-Term Effects of the Deception

The success of Operation Glimmer and other D-Day deceptions influenced military strategy well beyond the Normandy landings. The operation demonstrated the crucial role of electronic warfare and radar deception in modern military operations.

German forces continued to maintain substantial defensive positions in the Pas-de-Calais region for weeks after D-Day, believing a second, larger invasion might still occur there. This misallocation of resources weakened their ability to counter the actual Allied advance from Normandy.

The techniques pioneered in Operation Glimmer became part of standard military doctrine in subsequent conflicts. The concept of creating phantom armies using electronic signals and limited physical resources proved extremely cost-effective compared to traditional military operations.

Military academies worldwide still study Operation Glimmer as a classic example of how relatively small-scale deception operations can have disproportionately large strategic impacts when properly executed.

Operational Reflections and Historical Significance

Operation Glimmer stands as one of the most successful deception operations during World War II. Together with Operations Taxable and Big Drum, it created a smoke screen of confusion that significantly contributed to the success of the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944.

The operation involved RAF Short Stirling bombers dropping metal strips (codenamed “Window”) along the French coast near Calais. This clever tactic confused German radar systems, making them believe a large naval force was approaching that area rather than Normandy.

Military planners had learned harsh lessons from the failed Dieppe Raid of 1942. That disaster showed the importance of deception and proper intelligence, lessons directly applied to the D-Day planning.

General Bernard Montgomery, who helped plan the overall invasion, recognized the critical nature of these deception operations. By drawing German attention and forces away from the actual landing sites, Allied troops faced less resistance during the initial assault phases.

The success of Operation Glimmer provides three key historical insights:

- Military Deception Value: Demonstrated how relatively simple technical means could confuse advanced defense systems

- Strategic Integration: Showed how smaller tactical operations supported the largest amphibious invasion in history

- Intelligence Coordination: Highlighted the importance of coordinated deception across multiple domains (air, sea, intelligence)

German intelligence services were overwhelmed with contradictory information, creating precious confusion during the critical hours of the landing operations.

Allied planners considered operations like Glimmer essential to reducing casualties and establishing the crucial initial beachhead that would eventually lead to victory in Europe.