Operation Atlantic was a Canadian military operation that began on July 18, 1944, alongside the British Operation Goodwood. Many people often mix this up with D-Day, which took place earlier on June 6, 1944, when over 150,000 Allied troops landed across five Normandy beaches: Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha, and Utah. Operation Atlantic was actually part of the follow-up campaign after the initial D-Day landings had secured a foothold in Nazi-occupied France.

The D-Day invasion marked a turning point in World War II, bringing together land, air, and sea forces in what became known as the largest amphibious invasion in history. While American forces faced heavy resistance at Omaha Beach, Canadian troops stormed Juno Beach as part of the massive coordinated assault. These brave soldiers pushed inland despite strong German defenses, beginning the liberation of Western Europe.

Operation Atlantic continued the momentum weeks after D-Day, as Canadian forces fought to capture key objectives south of Caen. This operation was crucial in maintaining pressure on German forces and preventing them from mounting an effective counterattack against the Allied beachhead.

Historical Context

The D-Day invasion marked a pivotal turning point in World War II, representing years of strategic planning and coordination among Allied forces. The massive amphibious assault on June 6, 1944, codenamed Operation Overlord, was the culmination of extensive preparation and deception tactics aimed at breaking through Hitler’s Atlantic Wall.

Lead-Up to D-Day

World War II had been raging for nearly five years by 1944. After Germany’s conquest of France in 1940, Hitler established the Atlantic Wall—a series of coastal fortifications stretching from Norway to Spain.

Allied forces had already gained experience with amphibious operations in Sicily and Italy, but these were just stepping stones toward the ultimate goal: liberating Western Europe.

In 1943, Allied planners formed COSSAC (Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander) to begin developing invasion plans. By early 1944, SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) was established with General Dwight D. Eisenhower as Supreme Commander.

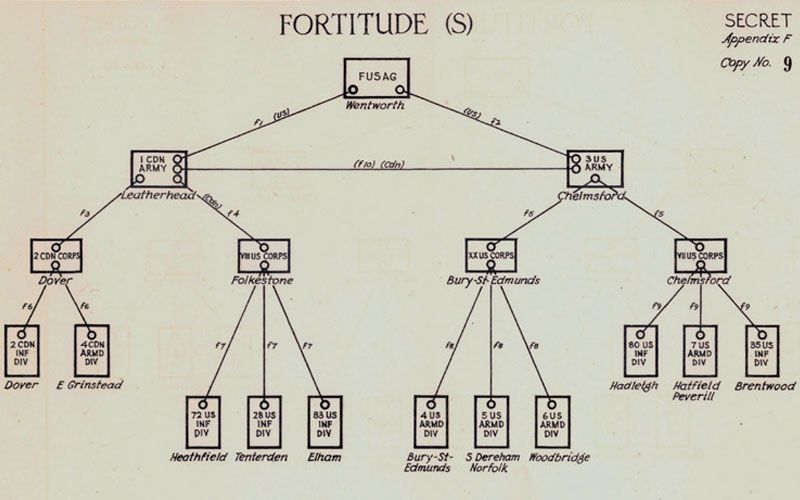

The Allies employed elaborate deception operations, particularly Operation Fortitude, to convince Germans that the main attack would target Pas de Calais rather than Normandy.

Strategic Importance of Normandy

Normandy offered several critical advantages for the Allied invasion. Its beaches were within range of air cover from England, a crucial factor for protecting landing forces.

The region provided access to French ports needed for supplying the invasion force. Once secured, Normandy would serve as a foothold for pushing inland toward Paris and eventually into Germany.

German defenses in Normandy, while formidable, were less concentrated than at Pas de Calais, which Hitler and many German commanders believed was the most likely invasion site.

The varied terrain of Normandy—with its beaches, cliffs, and bocage (hedgerow) countryside—presented challenges but also opportunities for Allied forces to establish defensive positions after landing.

Allied Forces Preparation

The invasion required unprecedented coordination between American, British, Canadian, and other Allied forces. Over 156,000 troops would land on five designated beaches: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword.

Training was intensive and specific. Soldiers practiced beach landings using specialized equipment like amphibious tanks and portable harbors called “Mulberries.”

Allied air forces conducted bombing campaigns to weaken German infrastructure and defensive positions. Naval forces prepared to transport troops and provide artillery support during the landings.

Timing was critically important. Planners needed specific conditions: a full moon for visibility, low tide to expose beach obstacles, and favorable weather. Eisenhower made the difficult decision to launch on June 6 despite marginal weather conditions, catching German forces somewhat unprepared.

Planning and Intelligence

The success of Operation Atlantic hinged on meticulous planning and reliable intelligence gathering. Allied commanders spent years developing strategies and collecting critical information about German defenses along the Atlantic Wall to maximize their chances of success.

Operational Strategy

Operation Atlantic was carefully planned as part of the larger D-Day invasion strategy. General Dempsey finalized the operation on July 13, 1944, with General Montgomery approving it two days later on July 15. The primary objective was to bypass Caen from the east, which had become a stronghold of German resistance.

Allied planners analyzed tides, terrain, and German fortifications extensively. They developed multiple contingency plans, including feints and raids along the Atlantic coast, to confuse German forces about the actual landing locations.

General George C. Marshall played a crucial role in coordinating American resources and strategy. His leadership ensured that troops and supplies were ready when needed for the complex operation.

Covert Operations

Intelligence gathering was vital to D-Day planning. The first breakthrough in decoding German communications occurred in Poland before the full rise of Nazi Germany. This intelligence capability, later known as “ULTRA,” provided crucial insights into German plans and movements.

The French Resistance supplied valuable on-the-ground intelligence about German troop movements and defensive positions. These resistance networks helped identify weaknesses in the Atlantic Wall and reported on German force concentrations.

Allied aerial reconnaissance missions photographed the entire coast to map German defenses. These images allowed planners to create detailed models of the invasion beaches and surrounding areas for training purposes.

German Defenses

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, fresh from his campaigns in North Africa, was tasked with strengthening the Atlantic Wall – Hitler’s “Fortress Europe.” Rommel recognized the vulnerability of the Nazi position and worked tirelessly to improve coastal defenses.

The Atlantic Wall stretched from Norway to Spain with varying levels of fortification. It included bunkers, artillery positions, machine gun nests, and extensive minefields both on land and in the water. Rommel’s strategy involved stopping the Allies at the beaches, believing this was the only way to prevent a successful invasion.

German forces positioned several Panzer divisions inland as a mobile reserve. Hitler maintained personal control over these armored units, which would later prove a critical mistake during the actual invasion.

Operation Neptune

Operation Neptune served as the naval component of Operation Overlord, representing the largest seaborne invasion in history. Under the command of Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsay, this massive amphibious assault began on June 6, 1944, with naval forces landing over 132,000 ground troops on the beaches of Normandy.

Naval and Air Support

The success of Operation Neptune relied heavily on naval and air support. Allied naval forces included five assault forces and two follow-up forces, consisting of warships from eight different nations. They provided crucial naval gunfire support to suppress enemy defenses before and during the landings.

Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers positioned themselves offshore to bombard German fortifications along the Normandy coast. This naval bombardment was essential in weakening enemy positions and creating opportunities for landing troops to establish footholds.

Air forces played an equally vital role. Thousands of Allied aircraft conducted bombing runs against German coastal defenses and transportation networks. They also provided air cover for the invasion fleet, ensuring German aircraft couldn’t disrupt the landings.

The Amphibious Assault

The amphibious phase began in the early hours of June 6, 1944. Landing craft of various types transported troops to five designated beaches: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword.

Naval Combat Demolition Units worked to clear obstacles placed by Germans to impede landing craft. These brave teams faced intense enemy fire while removing mines and barriers.

The operation involved an impressive array of specialized landing vessels. Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI) transported troops, while Landing Craft, Tanks (LCT) delivered armored vehicles directly to the beaches. Larger Landing Ship, Tanks (LST) carried heavy equipment and vehicles.

Weather conditions nearly caused a postponement, but Admiral Ramsay and General Eisenhower made the critical decision to proceed despite rough seas.

Establishing the Beachhead

Once ashore, troops worked to secure and expand their positions. Naval forces continued providing crucial fire support as soldiers pushed inland. Communication between ships and ground forces was maintained through specially trained naval liaison officers.

Supply ships brought essential materials to support the expanding beachhead. Engineers rapidly constructed temporary harbors known as “Mulberries” to facilitate the unloading of supplies when permanent ports weren’t yet available.

Naval vessels maintained defensive positions offshore, protecting the vulnerable landing areas from potential German naval counterattacks. This naval shield was vital during the first critical days of the operation.

By the end of D-Day, despite heavy resistance at beaches like Omaha, Operation Neptune had successfully landed Allied forces on Continental Europe. This naval achievement marked the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany’s occupation of Western Europe.

The Beaches of Normandy

The Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944 involved landings across five distinct beaches codenamed Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. These carefully selected landing zones stretched across 50 miles of French coastline and became the battlegrounds where the fate of World War II would begin to turn.

Utah Beach Operations

Utah Beach, the westernmost landing zone, saw the U.S. 4th Infantry Division come ashore with relatively light resistance compared to other beaches. Strong currents pushed landing craft about 2,000 yards south of their intended landing spots. This navigation error proved fortunate as troops encountered fewer German defenses.

The Americans quickly moved inland, establishing a beachhead and connecting with paratroopers from the 101st Airborne who had dropped behind enemy lines hours earlier. By day’s end, more than 20,000 troops and 1,700 vehicles had landed at Utah with fewer than 200 casualties.

Key objectives included securing beach exits and establishing routes inland. Despite some scattered resistance at fortified positions, Utah Beach operations progressed more smoothly than planners anticipated.

The Battle for Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach witnessed the bloodiest fighting of D-Day. The U.S. 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions faced formidable German defenses, including units from the experienced 352nd Infantry Division not known to Allied intelligence.

The first waves met devastating fire from cliffs overlooking the beach. Many Landing Craft, Infantry (LCIs) never reached shore intact. Soldiers faced a brutal gauntlet across 300 yards of open beach with minimal cover except for a thin seawall.

Small groups of determined soldiers gradually worked their way up the bluffs. Colonel George Taylor famously told his men, “Two kinds of people are staying on this beach: the dead and those who are going to die. Now let’s get the hell out of here!”

By nightfall, the Americans had secured only tenuous footholds. Casualties at Omaha numbered over 2,000, but the beachhead held against all odds.

British and Canadian Assaults

British forces landed at Gold and Sword beaches while Canadian troops assaulted Juno Beach. The British 50th Division at Gold Beach overcame initial resistance and advanced nearly 6 miles inland by day’s end.

At Juno, Canadian forces faced challenging obstacles, including rough seas and strong defenses. Despite these difficulties, they pushed farther inland than any other Allied force on D-Day. The Canadian 3rd Infantry Division cleared coastal towns and established crucial beachheads.

British troops at Sword Beach came within 3 miles of Caen, a key objective, before being halted by German counterattacks led by armored units. Special tanks called “Hobart’s Funnies” proved valuable in overcoming beach obstacles.

The British and Canadian forces successfully secured their assigned beaches, though key towns like Caen remained in German hands.

Airborne Divisions

Allied airborne forces played a critical role in the D-Day invasion, with over 18,000 paratroopers dropping into Normandy to secure key objectives before the beach landings began. Three airborne divisions—the American 82nd and 101st, along with the British 6th—were tasked with capturing strategic locations.

Paratrooper Insertion

The airborne assault began shortly after midnight on June 6, 1944. C-47 transport planes carried thousands of paratroopers across the English Channel under the cover of darkness. Many aircraft faced intense anti-aircraft fire, causing pilots to take evasive action.

Weather conditions and enemy fire disrupted drop patterns significantly. Paratroopers landed scattered across the Norman countryside, often miles from their intended drop zones. Some units reported only 10% of their men assembled at initial rally points.

Despite the confusion, the scattered nature of the drops actually created widespread chaos among German defenders, who couldn’t determine the size or objectives of the airborne forces.

Securing the Inland

The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions secured the western flank of the invasion area. Their primary objectives included capturing key towns, crossroads, and bridges at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula.

The 101st focused on securing exit routes from Utah Beach, while the 82nd targeted strategic crossings over the Merderet River. Although widely dispersed, small groups of paratroopers formed ad-hoc units and began accomplishing their missions.

The British 6th Airborne Division operated east of the Orne River, tasked with protecting the invasion’s eastern flank. They successfully captured vital bridges and disabled coastal batteries threatening the naval approach.

The cost was significant. By August 1944, the 101st Airborne had 1,240 casualties, and the 82nd Airborne Division had 1,259. Despite these losses, the airborne operations proved essential to the success of the overall Normandy invasion.

Leadership and Command

The success of Operation Atlantic and the broader D-Day invasion hinged on effective leadership at multiple levels. Strategic decisions by top commanders shaped the planning, execution, and follow-through of these complex military operations.

Allied Command Structure

General Dwight D. Eisenhower served as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, overseeing the coordinated efforts of 12 nations. His leadership was crucial in managing the massive operation code-named Overlord, which included Operation Atlantic.

General Omar N. Bradley commanded the US First Army, working alongside the British Second Army within General Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. This command structure ensured coordinated movement across the invasion beaches.

Admiral Bertram H. Ramsay directed naval operations, managing the enormous fleet that transported troops and provided crucial fire support. His naval expertise proved vital to the landings’ success.

The command structure benefited from strong political backing from leaders like Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt, who provided resources and diplomatic support necessary for such a massive undertaking.

German Command Response

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, as Commander-in-Chief of German forces in Western Europe, faced the immense challenge of defending the Atlantic Wall against the Allied invasion. His strategic flexibility was limited by Hitler’s direct interference in tactical decisions.

General Erwin Rommel, known as the “Desert Fox,” commanded Army Group B and was responsible for defending the Normandy coastline. He advocated for stopping the Allies at the beaches, fortifying coastal defenses with obstacles and mines.

The German command suffered from divided authority. Hitler’s insistence on personally approving major movements of armored reserves critically delayed effective counterattacks during the crucial first days after D-Day.

Communication breakdowns plagued the German response. Many senior commanders were away from their posts when the invasion began, including Rommel who was visiting his wife in Germany on June 6th.

Support and Logistics

The success of D-Day relied heavily on an unprecedented logistical effort that moved millions of troops, vehicles, and supplies across the English Channel. Behind every combat soldier were approximately nine support personnel handling the complex network of supplies and medical care.

Supply Chain Management

The Allied forces assembled an impressive supply chain for Operation Overlord, involving over 7,000 ships and 4,000 landing craft. These vessels transported not only soldiers but also vehicles, ammunition, food, and construction materials. The 1st Infantry Division, which landed at Omaha Beach, required constant resupply of ammunition and equipment to maintain their advance inland.

American logistics operated primarily through Omaha and Utah beaches. When rough seas threatened to disrupt supply lines, engineers constructed artificial Mulberry harbors. Though a storm destroyed the American Mulberry, beach operations continued.

The Coast Guard played a vital role, piloting landing craft through dangerous waters and maintaining the flow of supplies from ships to shore. Their expertise in navigating difficult coastal conditions proved essential to the operation’s success.

Medical and Evacuation Planning

Medical planning for D-Day involved a comprehensive system to treat casualties and evacuate the wounded. Field hospitals were established near the beachheads, with medical personnel landing shortly after the first waves of troops.

The evacuation chain began with combat medics providing immediate first aid. Wounded soldiers were then moved to beach clearing stations before transport to hospital ships waiting offshore. The Coast Guard assisted in many of these evacuations, navigating landing craft through enemy fire to bring the wounded to safety.

Blood supplies, surgical teams, and medical equipment were carefully distributed throughout the invasion force. Despite challenging conditions, this system successfully treated thousands of casualties during the first days of the invasion.

Outcome and Impact

Operation Atlantic and the broader D-Day campaign fundamentally altered the course of World War II, creating a crucial western front that divided Nazi forces. The Allied success in Normandy marked the beginning of the end for Hitler’s regime in Western Europe.

Opening the Second Front

The Normandy invasion fulfilled the Soviet Union’s long-standing demand for a second front in Europe. Since 1941, Soviet forces had borne the brunt of fighting against Nazi Germany. Stalin had repeatedly pressed his western allies to open another front to divide German military resources.

By June 1944, the Allied landings delivered on this promise. German divisions that might have reinforced the Eastern Front were instead tied down in France. This military pressure from the west provided meaningful relief to Soviet forces advancing from the east.

The second front also demonstrated Allied unity and commitment to defeating Nazi Germany through coordinated action. It represented the fulfillment of strategies developed at several major Allied conferences, including Tehran and Casablanca.

Strategic Advancement in Europe

The success of D-Day and subsequent operations like Atlantic enabled the Allies to establish a firm foothold in Northern France. By late August 1944, Allied forces had liberated Paris and pushed eastward toward Germany itself.

The Normandy campaign created momentum that couldn’t be reversed. Though German forces mounted a significant counteroffensive in the Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge) in December 1944, they couldn’t dislodge the Allied presence in Western Europe.

The campaign also gave Allied forces control of crucial ports and infrastructure. Capturing Cherbourg by June 27 provided vital supply lines to support the ongoing advance. Meanwhile, British forces secured Caen by July 9, though later than planned.

By spring 1945, Allied advances from both east and west led to Germany’s complete defeat, ending the war in Europe.

Legacy of D-Day

D-Day fundamentally changed the course of World War II and left a lasting impact on military strategy, international relations, and collective memory. The invasion marked the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany in Western Europe.

Military History Significance

D-Day represents one of the most significant military operations in history. The June 6, 1944 Normandy landings demonstrated the effectiveness of combined air, sea, and land operations at an unprecedented scale. Over 156,000 Allied troops landed on five beaches, making it the largest amphibious invasion ever attempted.

The operation’s success proved that carefully planned, massive-scale invasions could overcome heavily fortified positions. Military planners still study the extensive preparation, deception tactics, and logistical achievements of Operation Overlord.

D-Day accelerated the defeat of Nazi Germany, opening a crucial Western Front that divided German forces. Within eleven months of the landings, the Allies achieved victory in Europe.

The beaches of Normandy now serve as memorial sites, honoring the sacrifice of Allied troops who fought to liberate Europe from Nazi occupation.